ETHICS AND THE REVELATION OF CREATIVITY

By Levin A. Diatschenko

[Above] Lake Pedder, Tasmania, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

ETHICS are the outcome of a metaphysical realisation. People who are propelled through life by a strong ethical motive have sensed something intuitively about themselves. Ethics are the implications -- a logical reaction or code based upon the new, larger truth.

The realisation is this:

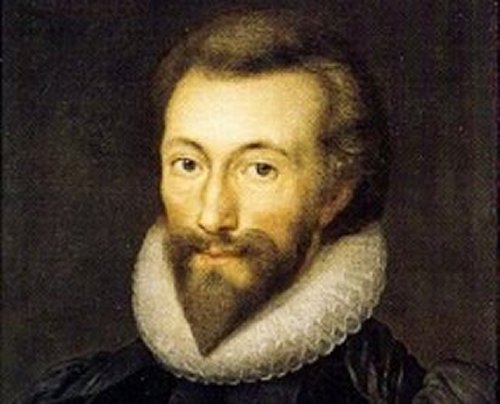

"No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never seek to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee." John Donne (1573-1631).

For the 1600s this extract is remarkable, and even more so considering it remains just as urgent a perception today. Of course, in the present, it would usually be worded differently, with 'Humankind' substituting for 'Mankind', to clarify the idea as non-sexist.

As a realisation (or even as a working hypothesis) the above asserts that each life is part of a larger synthesis. In the wake of this idea, 'selfishness' becomes illogical as it eventually harms the new, larger sense of self. Every person becomes a symbol or microcosm of Humanity. Murder becomes suicide and suicide becomes murder. John Donne, the English priest and poet who wrote the above, wrestled with suicidal urges all his life. But he never went through with it. Perhaps the reason was an ethical one?

Donne's idea has been 'updated' today to include all life, not just human life. Concerns for the health of the Earth is one example. But while it has been updated, it is still far from outdated.

[Above] John Donne (Artwork by Isaac Oliver, 1616)

"The greatest thing," said John Ruskin, "a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what he saw in a plain way ... To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion - all in one". Ruskin did not make such a grand statement as a detached critic. Helen Durant notes in The Beacon: "John Ruskin was a pioneering conservationist and foresaw the 'greenhouse effect' more than 100 years ago." Globalisation and global warming, if nothing else in modern times, has also proven John Donne's observation about interconnectedness as not just poignant, but indeed prophetic. The bell is tolling for all of us.

But poetry is not merely the written result of intuitive breakthroughs. It is rather a technique of approaching the intuition, that mysterious part of the mind from which all of humanity's breakthroughs come. I have read before about the existing puzzlement over how such a great poet and thinker as W.B. Yeats could at the same time have been gullible enough to get involved in The Golden Dawn and other secret and non-secret magic societies of his time. One justification is that he regarded the practice of magic as a form of poetry. But maybe he wasn't gullible. Maybe he was smarter than most of us, and, perhaps, poetry is in fact a form of magic. When criticised about this, Yeats wrote: "If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book, nor would The Countess Kathleen ever have come to exist. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write".

The well-known science fiction writer Kurt Vonnegut also touched on this concept in Palm Sunday:

"Literature is holy to me […] Meditation is holy to me, for I believe that all the secrets of existence and non existence are somewhere in our heads - or in other people's heads.

And I believe that reading and writing are the most nourishing forms of meditation anyone has so far found.

By reading the writings of the most interesting minds in history, we meditate with our own minds and theirs as well.

This to me is a miracle."

Incidentally, Vonnegut also had ideas of taking his own life. He attempted suicide in 1985. Afterwards he wrote about the topic in his works, once citing a letter that a young girl had written to him, asking him please not to kill himself.

Depression, despair and suicide are not uncommon in the arts. The Van Goghs and Hemingways are well known and even form part of the glamour surrounding the artistic hero. Mozart and Beethoven both suffered terrible bouts of depression. So did John Ruskin. Tolstoy confessed his dilemma in Anna Karenina, through Levin, Tolstoy's alter ego: "And Levin, a happy father and a man in perfect health, was several times so near suicide that he hid the cord, lest he be tempted to hang himself, and was afraid to go out with his gun, for fear of shooting himself." Tolstoy actually made a vow that showed his seriousness in finding the meaning of life. He once wrote: "Without knowing what I am and why I am here, life is impossible".

[Above] Title Unknown (Artwork by artist unknown, year unknown)

But there is a reason that the artists, writers, poets and the like are a part of society that is so susceptible to despair. Vonnegut gave his theory that the artists' roles in society are like the canaries that miners once used to take into the mines in order to see if the air was alright; if it wasn't, a canary would die quickly as an indication. This would save the miners' lives. The more sensitive amongst us often find their way to the arts as a form of expression, hence the stereotypical depictions of artists as emotionally troubled. But, it is this same sensitivity that can enable the artist to 'sense' the hidden principles of life, such as that expressed by John Donne above. Tolstoy, shared the vision: "Man lives consciously for himself, but is an unconscious instrument in the attainment of the historic, universal, aims of humanity".

This is the magic of art. Oftentimes wealth and happiness seem to be its sacrifice.

Eliphas Levi, in his classic 1800s work on Western magic, Transcendental Magic, Its Doctrine and Ritual, describes what is called the 'magnetic chain', the goal of ritual magicians. It is a chain of enthusiasm and thought, which becomes the nucleus for social movements, catching people up in its whirlwind. It is perpetuated by speech and common symbols, among other things.

|

He writes, "The magic chain of speech was typified by chains of gold, which issued from the mouth of Hermes. Nothing equals the electricity of eloquence." Later he writes, "Printing is an admirable instrument for the formation of the magic chain by the extension of speech […] and the aspirations of thought attract speech."

In any case, creativity is one way of becoming aware of your thoughts. This is also what meditation is. Becoming aware of your mental activity is also an act of responsibility in the same way that becoming aware of your actions and words are, in regard to how they affect others. While the Catholic makes his or her confession to a priest hidden on the other side of a screen, the artist makes his or her confessions to the world at large just on the other side of the novel, poem or canvas. While the religious devotee prays to God for humanity, the ethical artist prays to god in humanity, once again through her or his works.

Creative arts are an avenue and training ground for the imagination. The imagination is not something that merely makes things up that do not exist; it is a kind of sonar device which discovers and defines invisible or abstract principles, and then 'clothes' them in images, so that we can see them. Words, for example are clothes for the 'invisible human' we call the mind. Generally, most people cannot hear or see thoughts until they are transcribed into, or 'clothed', in words. |

[Above] Eliphas Levi (Photo by photographer unknown, year unknown)

The metaphysical poets like Donne and Yeats are well known for their use of the conceit. I find the literary tool called the conceit described in interesting ways. Here are some examples of how most sources define it: "a far-fetched comparison" (The Standard English Desk Dictionary, Funk & Wagnalls); "an elaborate, fanciful metaphor, esp. of a strained or far-fetched nature - the use of such metaphors as a literary characteristic, esp. in poetry" (American Psychological Association, from Dictionary.com).

I even find this in Wikipedia.org:

"Helen Gardner observed that 'a conceit is a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness' and that 'a comparison becomes a conceit when we are made to concede likeness while being strongly conscious of unlikeness'. […] An often-cited example of the metaphysical conceit is the metaphor from John Donne's 'The Flea,' in which a flea that bites both the speaker and his lover becomes a conceit arguing for the depth of their union."

" 'Oh stay! three lives in one flea spare

Where we almost, yea more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage-bed and marriage-temple is.'"

So, conceits are described as fanciful and far-fetched, yet most of the revelations we get from poetry are the results of such surprising comparisons. The question is, can a flea possibly represent more than a flea? The answer comes by asking, can a piece of cloth represent more than a piece of cloth? If I find a piece of cloth and burn it, nobody will care. But if the cloth is painted to become a national flag, it suddenly means far more -- and then a mere piece of coloured cloth causes emotional changes in people whenever they see it displayed, let alone burned. Each Australian flag is a different piece of cloth, but because they contain the same symbol, people see all of these flags as the same object (note the magical chain in this). And when it burns, the patriotic onlooker actually feels as if something has been done to him.

Donne's flea was the romantic symbol of a nation of two.

Two people could be completely different culturally, sexually, financially and physically; yet, they are both analogous to each other on one level: they are both "involved in Mankinde". The comparison is stretched, no doubt, but true nevertheless.

The U.N. is analogous to the flea in that it contains a little of every one of us within it. (This reminds me of the Old Testament's "coat of many colours".) Ideologically, within that symbol, there is one fused and larger awareness that we are all part of - like the fused blood of the two lovers. The conceit, rather than being far-fetched and fanciful, is the spiritual poet's tool to look past surface differences and see the common truth within.

|

Analogy opens the doors of perception and reveals the unity of consciousness that gives birth to Ethics.

To this, let us add some Yeats, from The Celtic Twilight: "Hope and Memory have one daughter and her name is Art, and she has built her dwelling far from the desperate field where men hang out their garments upon forked boughs to be banners of battle. O beloved daughter of Hope and Memory, be with me for a little".

Francis Bacon, another great magician/writer of the Rosicrucian creed, said that analogies are "not only similitudes (as men of narrow observation may conceive them to be), but plainly the same footsteps of nature treading or printing upon different subjects and matters." Analogies (created through imagination) are different clothes for one invisible law. It is the sensing of that unclothed law that is Intuition. The clothes are mental and have served their purpose - we are afterwards left with the 'naked truth'. |

[Above] Francis Bacon (Artwork by artist unknown, year unknown)

Furthermore, Eliphas Levi also defined magic as "the science of analogies".

If we do decide to look at a country as being one great synthetic life, the role of art and literature comes to light in a very straightforward way. The arts, ideally, are evidence of that organism trying to become Self-conscious (referring to the Higher Self). You might say that the arts are that part of the organism which creates consciousness. It would explain, then, why the art communities throughout history have always been amongst those promoting peace and condemning war, why they are traditionally sympathetic towards the downtrodden. When George Orwell wrote Down And Out In Paris And London, he was symbolically saying to all his readers, "Look at this part of society, the poor". It is synonymous with saying: "Look at this part of yourself. You've neglected it". Moreover, any individual nation that is ignorant of the problems concerning its indigenous population is like one person who dislikes a part of himself - a part that he has abused because of other obsessions. The same goes for animals and the environment.

Theodore Sturgeon, the great science fiction writer, approaches this idea of united life in his novel More Than Human, where five misfits find themselves disadvantaged when on their own, each with physical and mental disabilities. But when they find each other, they become a single cooperative life form called "Homo Gestalt", the next step in evolution. They still find 'themself' alone, however; it is only after they learn the bridging qualities we call morals and ethics that this Homo Gestalt is able to become aware of others like itself. In the same novel, Sturgeon also gives us his own interesting definitions of morals and ethics: morals are society's code for individual survival. Ethics are an individual's code for society's survival.

|

Under this definition, a society without morals cares not for its people and a person without ethics cares not for their community. The underlying effect is separation. The larger being becomes fragmented. Every human becomes an island.

Edward De Bono, in his book The Mechanism of Mind discusses the way poetry moves people, comparing it to an intellectual revelation - such as a scientist's 'eureka moment' - and even to the way a joke's punch line makes people laugh. He puts it down to lateral thinking, or approaching a subject from a new and seemingly illogical angle, for the purpose of 'breaking through' the beaten path of circular thought. An example might be using a flea to represent the fusing power of love ...

Here is a joke: Buddha walks into a pizza shop and says: "Make me one with everything!" |

[Above] Alice A. Bailey (Photo by photographer unknown, year unknown)

There are three components to this joke. One is Buddha, who represents the divine; one is a pizza shop, which represents the mundane. These first two components are like the two far-fetched comparisons of a conceit. The third aspect is the punch line - "Make me one with everything!" This sentence, like Donne's usage of the metaphorical flea, unites inside it both the divine and the mundane, i.e. it has a double meaning, applying to both. In Donne's poem there are two very romantic lovers and then there is a flea, something usually thought of as annoying rather than romantic. But through the usually mundane act of a flea biting the lovers, it suddenly represents something divine, the spiritual union of two souls into one.

This trinity principle, revealed through metaphor, also comes out in religious doctrine: Hercules's father was a God but his mother was a mortal of Earth, making Hercules a link or fusion of both; Christ has almost exactly the same circumstances. (This is a hidden meaning of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, or Siva, Visnu and Brahma). In politics, the U.N. would be the mutual link or fusion between otherwise very separated countries.

|

Ethical and Spiritual Art also performs this function of breaking borders, crossing boundaries and creating new realities. Since thoughts need to be transcribed into pictures or words so that people can express their thoughts, so it would be with a macrocosmic person. To understand an organism as large and complex as a nation would take a lot of words -- a whole era of literature, in fact, not to mention newspapers and magazines, and so forth. As we go deeper into the mind, we come to the place of abstract thought and ideas, thoughts that are not necessarily attached to specific objects or events. These thoughts are not published as quickly, nor are they distributed as widely. Thought is slower up there, but each thought has a longer lifespan. In the macrocosmic life, this is surely manifested in the ethical and spiritual aspirations of the arts, with attention to the human condition rather than to one group of humans' current political concerns. |

[Above] Title Unknown (Artwork by artist unknown, year unknown)

A person biased towards material reality finds it easier to engage in material thoughts, that is, considering physical objects and events. But that person would have to slow his or her mind down and concentrate if she or he wants to ponder on an ideal or abstract concept - like love or freedom or the Soul. When a person holds his attention firmly there, at that level of thinking, this is also called meditation. For the giant organism called a nation, the passage of awareness from material thought to meditative thought is the journey from television, newspapers and radio over to dusty bookshops and hole-in-the-wall galleries and poetry readings.

Homer's Odyssey is not front-page stuff. It is a slow giant that is older than all of us, containing abstract concepts and ideas that still have not died.

Concrete thought is a prisoner of time; intuitive and abstract thought transcends time. Homer has been dead so long that nothing is known about him except that his name is given as the author of The Odyssey and The Iliad. There are a few theories, but nobody knows for sure, in which century he even lived. His books, however, remain in print today.

From the vantage point of abstract thought, one can refrain from being led around this way and that by the daily news, which might be likened to a performing magician's hands. The 'magicians' referred to, of course, are those who control the mass media, showing us only what they want us to see. The constant movement of these 'hands' (or emphases) makes it difficult for us to retain the more important information.

From the said abstract vantage point, one can retain more in one's memory, and view the idea or ideal that caused each day's news. In fact, most memory-training systems rely on associating the object or event to be remembered with its abstract quality. John Donne's flea will now be easier for us to remember than any other flea. Many separate events might be difficult to remember or understand, but if they are all connected under the umbrella of The Russian Revolution, say, or even more abstractly: Socialism, then the events fit into a whole and are retained more easily.

|

To say that the arts are a needed part of a culture is synonymous with saying a person needs to develop the intelligent ability to understand abstract concepts. We need to be aware and able to formulate ideas in order to express them. So, as the arts receive new ideas from a mysterious - perhaps spiritual - bridge called the intuition, which leads to the source of ideas, the arts then (potentially) articulate and explore these ideas, clothe them with metaphors - conceits -- and pass them out to the concrete mind. The ideas become ideals and then get translated into the actions of the organism.

On this receiving of ideas from a larger awareness, Ruskin said: "Really great people have a curious feeling that the greatness is not in them but through them. Therefore they are humble". |

[Above] John Ruskin (Photo by photographer unknown, year unknown)

It is this that William Burroughs must have meant when he said, "Artists to my mind are the real architects of change, and not the political legislators who implement change after the fact".

Annie Besant, the theosophist, feminist and social revolutionary said, "No weightier responsibility can any take, no more sacred charge. The written and the spoken word start forces none may measure, set working brain after brain, influence numbers unknown to the forthgiver of the word, work for good or for evil all down the stream of time".

A perfect example of an artist as architect for change, and a champion of ethical and moral drive, is the poet, artist, critic and social revolutionary, John Ruskin. In her article "John Ruskin - A Forerunner", Helen Durant writes: "It is indeed possible to see Ruskin as an important influence on English social legislation for much of the twentieth century - notably on bills introduced by the government Clement Attlee was eventually to lead. Ruskin's ideas came to shape much of our thinking today and his words are as relevant now as they were in his own life."

To be sure, his influence was wide. Gandhi said, "I believe that I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflecting on the great book of Ruskin's, Unto This Last, and this is why the book so captured me and made me transform my life". Of course, in the process, Gandhi also transformed India, as well as every mind that is inspired by Gandhi.

Tolstoy described Ruskin like this: "Ruskin was one of the most remarkable of men, not only of England and our time but of all countries and all times. He was one of those few men who think with their hearts, and so he thought and said not only what he himself had seen and felt, but what everyone will think and say in the future."

Ruskin often said that the morals and values of a nation are explicitly visible in its art, and he argued that art and morality are fundamentally linked. If a society begins to compromise its morals, this suggests a similar compromise in the society's arts.

[Above] Ruskin On Money (Photos by photographer unknown, year unknown)

That the artists of the world are considered among its greatest thinkers is reflected in the museums and galleries each country has devoted to them, often in the name of national pride. We even put our poets on our currency. Borges is on the Argentinian currency; Yeats was on the 20-pound note of Ireland; Mary Gilmore and David Unaipon are on Australian money. However, anybody slightly familiar with the ideas of these great thinkers also understands the strange hypocrisy that the arts have become increasingly ignored in the grab for material wealth. The poet, once considered a noble calling, has degenerated in the public eye to an ineffectual dreamer. This is the equivalent of a macrocosmic being refusing to acknowledge the pangs of its conscience. It is also a refusal to think deeply. Indeed, the somewhat subliminally, though unanimously accepted ideal of consumerism, has degraded art, making money its chief measure of value, a fact realised in American Pop Art of the 1980s.

This has oftentimes led to fragmentation and competitiveness in the arts community rather than cooperation, reflecting the loss of the perception of Unity. Fame, it seems, has now become the new end to which the arts are a means. Take Australian Idol and its effect on music, for example. The protective idea of Copywrite is another example, suggesting that because a person receives an idea, he should own it exclusively. It further implies that ideas themselves are subordinate to their carriers, to be used as currency rather than shared and acted upon for mutual betterment. Everybody vainly grabs for his or her own piece of truth, thereby treating it as property and fragmenting the macrocosmic life.

Notwithstanding the effects of materialism, the perspective of unity is growing beneath the surface of commercial press, and threatening to take over the old views of separation and conflict. One of the little evidences is cooperation in art, such as Creative Commons instead of Copywrite, and independent art.

|

Helena Roerich, the Russian writer and spiritual revolutionary (1879-1955) was one of the first people in the west to reject the idea of idea-ownership, when she wrote her fourteen volume Agni Yoga series (the Living Ethics). On the covers and title pages there is no author written; Roerich considered that the spiritual wisdom in its pages could not be the author's property.

Independent art comes from "the people" or the masses, and is therefore an expression of self-worth and self-respect by them. It is 'one of us' talking; to support it is to support yourself, to affirm that someone 'like you' is worth hearing out, or is capable of art.

It suggests that ethics make art non-elitist, and that it is morally beneficial, even therapeutic, to the egotistical artist. A sobering thought.

Here is an extract from an article called Self Publishing Indigenous Language Materials by Robert N. St. Clair, John Busch and Joanne Webb, from a Northern Arizona University site called Teaching Indigenous Languages. I find it reflects well today's climate in literature and publishing: |

[Above] Helena Roerich (Artwork by Yuri Moscalenko, year unknown)

"There are five major publishing giants in the United States [and the world, (Levin D.)], each of them known under hundreds of different names or signatures. They use one name for publishing textbooks, another for publishing romance novels, another for murder mysteries, and so on. Oil companies own four of these giants, and a movie studio owns the other. These companies are successful because they publish thousands of copies of books for a very low per-copy cost. They also have tax laws that support their business operations. In the past, it was difficult to compete with these giants. They had the money, the connections, and the distribution channels. Some of them even owned printing presses.

"Something interesting happened in the printing industry to change the publishing giants' advantages. The change came about because Frank Valenti, a lobbyist for the film industry, argued that new laws were needed to protect the movie and CD industries from pirating.

"Congress passed these laws, taking away many of the advantages that publishing conglomerates had over the small self-publisher. They were now forced to do short runs, which caused their costs to be substantially higher. This change was immediately noticed in the pricing structure of books. Paperbacks that previously sold for $6 now sold for $16. Small publishers have always done small runs of books. Now the large publishers were doing the same thing.

"Something else happened to the publishing industry. The tools of their trade, electronic publishing, were now available to everyone for under $2,000. Big publishing houses once paid $60,000 or more for their equipment. Now we have the same capabilities in our personal computers for a fraction of that cost."

|

Nevertheless, the windows in the major bookstore chains around the world are all too often covered with a limited number of choices. This is 'dependent' publishing, where the writer depends on his sponsors, and the population depends on others to inform them of which ideas they ought to be exposed to. On top of this, the few large publishers have become more conservative with each year. Much of the adventurous material produced in the sixties, seventies and eighties would not be able to find a major publisher in more modern times. (There are exceptions, of course, such as Andrew McGahan's Underground.) This amounts to a blocking of ideas, again the spiritual equivalent of a clot, stopping circulation.

In Practical Occultism, the theosophist Helena P. Blavatsky talks of the "subliminal ideology" (a phrase I take from Dominic Dibble's speech Prisoners Of Reason) of competition in the West. She says: "All Western, and especially English, education is instinct with the principle of emulation and strife; each boy is urged to learn more quickly, to outstrip his companions, and to surpass them in every possible way. What is mis-called 'friendly rivalry' is assiduously cultivated, and strengthened in every detail of life." In contrast, she explains that an Eastern ashram sees its students as being "fingers on the same hand", and that students should be so sensitive to each other as to be like individual strings on a lute. |

[Above] Helena P. Blavatsky (Photo by photographer unknown, year unknown)

One might speak of competition being natural. There is a kind of competition that arises naturally; and there is also encouraged-but-unnecessary competition, which separates. In natural competition (being that there are only so many books one can read), the competition should - as a matter of responsibility - be one of ideas rather than authors. For example, it would be a selfish thing to try to have someone read my book instead of one by Kurt Vonnegut. Likewise, I am in no way suggesting a 'small publishers vs. large publishers' scenario. This is self destructive, and would lead to simply cutting tall poppies or judging by size. Any publishing house that channels new ideas and imaginations to wide audiences is fulfilling its spiritual responsibility in the world; any who sees producing books only as a means to cultivating money, is surely hindering art.

In a speech given at the London World Goodwill Seminar 2006 (Dispelling The Hype: The Quest For Authenticity), radical economist David Boyle tried to define Authenticity:

"I think it's about simplicity. I think when 70 percent of the nation [England] say they want to simplify their lives, then something is going on. I think it means 'unspun'. I think that the rise of poetry and reading groups is relevant to this. When almost all public discourse is trying to cajole or persuade us to do something - even the news is trying to persuade us to turn on again next week or stay on - I think poetry is one of the few kinds of authentic discourses that there are left."

I think this indicates that independent lovers of art are just as important as independent makers of art.

One might ask: if art fulfils this spiritual and ethical function in society, how and why does it differ from churches? The Christian churches, at least, generally emphasise morality and chastity far more than any other quality recommended by the New Testament. Art, however, emphasises truth -- as in "the truth will set you free". Kurt Vonnegut noted:

"For some reason, the most vocal Christians among us never mention the Beatitudes. But, often with tears in their eyes, they demand that the Ten Commandments be posted in public buildings. And of course that's Moses, not Jesus. I haven't heard one of them demand that the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes, be posted anywhere. 'Blessed are the merciful' in a courtroom? 'Blessed are the peacemakers' in the Pentagon? Give me a break!"

This over-emphasis on Old Testament traits, like strict morality, has led us to feel uncomfortable when we fall short of our moral ideal. When this happens we may not want to admit our faults; we may lie to ourselves. If others fall short of our ideals, we punish them for it, which does not make it easy for them to be honest either. So, in effect, by promoting dishonesty, the church has pushed away many honest people. Although often with good intentions at heart, the Church has thus inevitably attacked the arts out of fear of the truth. One example is the banning of the film Brokeback Mountain, a gay love story, in two US states, after the influential "Conference of Catholic Bishops" gave it an "O" rating for morally offensive. To ban a film because it shows gay lovers, as in Brokeback Mountain, is synonymous with not wanting to admit they exist; in other words, trying to hide the truth. Something, I might add, Christ advised against.

A last note on the power of the written word to unite people: From my perspective, I am writing these words right now -- not in your past. From your perspective, you are reading them right now -- not in my future.

|

So, we are both reading and writing this piece right now, notwithstanding the space and time that is apparently between us. Reading-writing is an impersonal pastime, but by no means a solitary one. Right now, you have my company, and I yours.

It is as if every person who has read, is reading, or ever will read a particular book or poem, is mentally inside a 'pocket' of time -- outside of normal time -- where they all sit together eternally as members of an audience, attending the same gathering. It is a gathering, moreover, that soldiers can never break up. Not unless they burn the books. |

[Above] Lake Pedder #2, Tasmania, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Alice A. Bailey, the famous occultist and promoter of unity, spoke of the "Seven Rays" or qualities that make up the universe (this is a concept existent in religion but communicated in this terminology first by Helena Blavatsky). Bailey called the fourth of these rays, the quality of "Harmony Through Conflict". This reminds me of two conflicting things brought together by metaphor, analogy, etc, as mentioned above. Bailey said that Humanity, as a whole, is currently under the influence of the fourth ray. This may or may not be the case, but the concept is very interesting today when considered in the light of Globalisation. Globalisation is causing many groups to become aware of each other, sometimes before they are ready or want to. This causes conflict in much the same way as Brokeback Mountain did, or as news to a capitalist that a billion people earn less than a dollar a day would. Climate change is another example of news that brings out conflicting desires.

The task, then, in true art and in all things ethical, is surely to see this 'collision of parts' as a first step to progress, an opportunity. Now that we have everyone together, albeit in conflict, the next step is to achieve Harmony. The strategy can be found through the ongoing personal, societal and universal development that occurs through the creative process.

Sources:

John Donne, Meditation XVII, 1947

(http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/ruskin/ruskinov.html) 2007

Wikipedia, Yeats (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Butler_Yeats). 2007

Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Palm Sunday. Dell Publishing. 1980.

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina. Penguin Classics. 1995

Leo Tolstoy Quotes, Brainy Quotes (www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/l/leo_tolstoy.html) 2007

Transcendental Magic, Its Doctrine and Ritual, Eliphas Levi. Kessinger Publishing. 1910

The Standard English Desk Dictionary, Funk & Wagnalls. 1989

American Psychological Association, from www.Dictionary.com. 2006

Wikipedia, Conceit (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conceit) 2007

W.B. Yeats, The Celtic Twilight. Kessinger Publishing. 2005

Francis Bacon, Advancement of Learning. Britannica Great Books. 1952

George Orwell, Down And Out In Paris And London. Penguin Modern Classics. 2000

Theodore Sturgeon, More Than Human. Millennium SF Masterworks S. 1980

Edward De Bono, The Mechanism of Mind. Penguin. 1987

Homer, The Odyssey. Britannica Great Books. 1952

Homer, The Iliad. Britannica Great Books. 1952

The Thylazine Foundation, Quotes Page (www.thylazine.org/quotes/) 2007

Annie Besant, Annie Besant, An Autobiography. Quest Books. 1999

John Ruskin-A Forerunner, Helen Durant in The Beacon, vol.LVIII, no.12 November/December 2000.

Agni Yoga, 1929. Published by the Agni Yoga Society. 1997

Self Publishing Indigenous Language Materials, Robert N. St. Clair, John Busch and Joanne Webb, from Teaching Indigenous Languages, (http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/TIL.html). 2003

Helena P. Blavatsky, Practical Occultism. The Theosophical Publishing House. 1999

Prisoners Of Reason, Dominic Dibble, at the World Goodwill Seminar, London 18th, 2006. The Lucis Trust.

Dispelling The Hype: The Quest For Authenticity, David Boyle, at the World Goodwill Seminar, London 18th, 2006. The Lucis Trust.

The New Testament, King James Version.

Cold Turkey, Kurt Vonnegut, in In These Times, Wednesday, May 12, 2004.

Movie Given Boot, News.com.au, 10 Jan 2006, from ant.sillydog.org/blog/2006/001025.php

Alice A. Bailey, A Treatise On The Seven Rays. Lucis Trust. 1988.

About the Writer Levin A. Diatschenko

|

Levin A. Diatschenko is thirty-one years old. He currently lives in Darwin, where he is working as a landscaper. In 2004, he published his first novel, The Man Who Never Sleeps, with Wolfty and Cliff. Most of the book has now become available to read online, with illustrations by the author, on Undergrowth.org. Recently, Levin was invited to speak at the National Young Writers' Festival in Newcastle. Levin also writes short stories and articles for various sites, especially Undergrowth.org, and is on the staff team. (Undergrowth is a collective of writers, artists and journalists). Levin Diatschenko's style of prose is very visual, sometimes surreal. The subject matter is chiefly a fusing of mysticism, theosophy and the esoteric in general, with daily living. |

[Above] Photo of Levin A. Diaschenko by Anna Corkhill, 2006.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.12 (June, 2007) |