OBSERVATIONS FROM THE 'REAL WORLD'

what it takes to be a writer-in-community

By Angela Costi

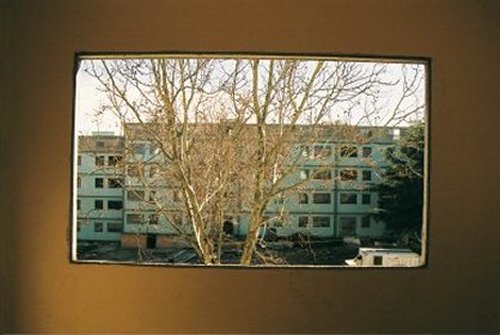

[Above] ReLOCATED - Postcard Image (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

Within Australia, there are a significant number of writers who channel their creativity, projects and enthusiasm within a community context. In dramatic contrast to the writer who may only have their personal world for company as they write their novel, these writers-in-community are constantly engaged with personalities, emotions, ideas and stories from a vast number of individuals called 'community'. This area of writing has produced a discipline, a practice and its own language, revealed in terms like 'community cultural development', 'community building' and 'social capital'. It is an area where the process is considered to be just as important as the outcome, and the outcome can range from a small self-published anthology of stories to a touring multi-media performance and exhibition. Writers, including myself, have worked with homeless youth, asylum seekers, public housing tenants, elderly Vietnamese and many, many other groups of people - unearthing hidden, disadvantaged, repressed or silenced voices.

|

Although altruism and self-sacrifice are not the ruling paradigms for working in this area, there is often a strong sense of social justice, which motivates writers to work alongside communities.

In my case, I hope that my work with communities goes some way towards redressing the considerable inequity within the creative arts, which favours work that has a commercial, marketable appeal over minority, alternative and financially depressed voices. In addition, I am motivated to engage in creative work that is mutually stimulating, that enriches me just as much as each member of the community. And this mutual exchange has taken place with just about every community project I've worked on - a period of 15 years with over 20 projects.

On a practical level, working within this area, as distinct from pursuing my own personal goals as a writer, has not been such a hard transition; through my cultural background (Cypriot-Greek), I am already in contact with some of the communities I have written for and with. Since my first commission in 1994, which was writing a play for young people from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern backgrounds, I have moved into larger cultural circles with projects involving over twelve cultural groups, some of which I'd previously had no point of connection with (such as Koori youth in regional Victoria). |

[Above] ReLOCATED (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

In my opinion, the process is paramount to the outcome. It's in the process where the real magic begins to happen, where I have the opportunity to challenge and be challenged, to learn and relearn, to gain another perspective that no amount of imagination on my part could ever evoke. In my community writing practice, there is an organic flow of exchange placing no one on a pedestal, no one in the teacher's chair and everyone in the spotlight. The personal rewards in this area can be immense - new interpretations, new voices, new friends and heart churning words. But it's an area with many points of negotiation. Probably more points than those found in publishing, where there is perhaps little more than an editor, a publisher and their literary colleagues to please. In contrast, when working with the community, there are often anywhere between fifty to five hundred, if not more, people you are working closely with. When I was writer-in-community at the now demolished Kensington Public Housing Estate (working on the reLOCATED arts project), I was answerable to approximately 1,500 tenants, not to mention the various governing and nonprofit bodies that were funding me.

The reLOCATED arts project

This project spanned a period of three years, involved far more than writing - it also involved administrating, advocating, facilitating, coordinating, curatorial work, directing, dramaturgy, coaching, editing, recording, researching, publishing, exhibiting, archiving ... and then there were the multitudes of visits to public tenants' flats and the conversations meant for my ears alone. This project, titled reLOCATED, had to somehow pay tribute to those tenants who were relocated from the Kensington Public Housing Estate, it had to capture their lives and their emotional truth it had to show the diversity within the diversity, and it had to be their farewell salute to Kensington, their home of many years. I felt the pressure, to say the least, and I felt the passion to write their stories and express their voices as honestly as possible. And although I went on an incredible journey, both personally and professionally, I needed to be always mindful that I was carrying the greater journey of the tenants and their loss, and this greater journey had to be carried with care and respect, and never compromised. I don't know whether I pleased all the tenants - there were so many of them and they were scattered across Victoria. I do know that those tenants I was in regular contact with were my point of reference, and through them I was accessing their wider community's thoughts.

[Above] ReLOCATED - Cung Van Nguyen (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

When I first arrived on the Housing Estate, it wasn't tenants that greeted me, rather it was the large demolition crane, the scaffolding and padlocked fencing. A sizable section of walkup flats (four storey buildings without lifts) were reduced to rubble, while another sizable section of the Estate felt like a ghost town, as flats were emptied and boarded up for 'stage 2 demolition'. The land on the Estate was a mishmash of awkward baldness (particularly the area where the 12 storey highrise, 72 Derby Street, used to stand), and cascading tresses of greenery (particularly near the embankment and Snake Gully Hill). When the crane wasn't making its wretched gnashes and grumbles, and the buildings were left as ruins, the silence on the Housing Estate was overwhelming. Where was the busy metropolis of high density living? They were in the throes of moving beyond their community borders, moving from balconies to courtyards, moving from rooftop views to grassy backyards, moving furniture, pets, babies ... into new suburban landscapes with varying degrees of emotion; from deep anxiety to high euphoria, from "can't wait to leave this place" to "I want to come back!" Altona, Ardeer, Braybrook, Coburg, Deer Park, Footscray, Shepparton, Laverton, Maidstone, Flemington, North Melbourne, Werribee, Yarraville ... individuals and households shifted, one by one, to spot-purchased public housing or other Estates.

|

The State Government's Office of Housing was prepared to give them three choices of relocation but within time limits. The land on which the Kensington Housing Estate once stood was earmarked for private development by the Becton group, and they had a predetermined timeline within which to get this new land development up and running. |

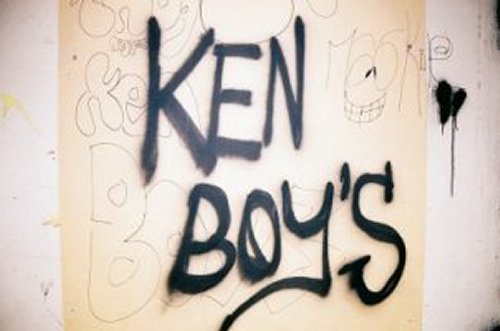

[Above] ReLOCATED - Ken Boys (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

The land is valuable in terms of its inner-city-urban location, and so the Government wanted to make money out of it, despite the unquantifiable cost to the existing community that lived there. As well as those tenants relocated beyond Kensington's boundaries, there were those left behind in the two highrise towers and the Durham Street walkup flats; living with the advent of refurbishment works and experiencing the loss of a familiar neighbourhood. Many of these remaining tenants were elderly and too frail to move.

Through City of Melbourne funding, I was given a 'writer-in-tenancy' opportunity at the Housing Estate. This tenancy allowed me to work from one of the rooms of a flat earmarked for demolition, and to work closely with Angela Bailey, who was the photographer-in-tenancy. As writer and photographer, we witnessed and documented the upheaval of the Housing Estate from about April 2001 to April 2002. We were fortunate in that our funding source did not censor nor impose an agenda on us.

|

It gave us wide scope to explore and examine through text and image this huge shift in demographic and social structure in a suburb with a population of 5000, where a great proportion were being relocated elsewhere. The simultaneous process of relocating, demolishing and renovating meant no easy access to people and communities. Their journey as community was now fragmented into the strong current of privatised development and progress in order to facilitate outreach connections, a reference group was established for us to meet with on a regular basis.

This group was made up of tenants and housing/tenant workers who were based at the Housing Estate. They proved to be an invaluable source of information for our project, connecting us to tenants that had been relocated to various suburbs in the West, and further to the North.

Our tenancies were initially for one year but were extended as it took time to build trust, to develop friendships, and to bond with a community that was understandably wary given the misspent over-analysis already imposed on them (from the bureaucratic, inaccessible surveys conducted by door knockers to the dramatised and na´ve drug-fixated media attention). |

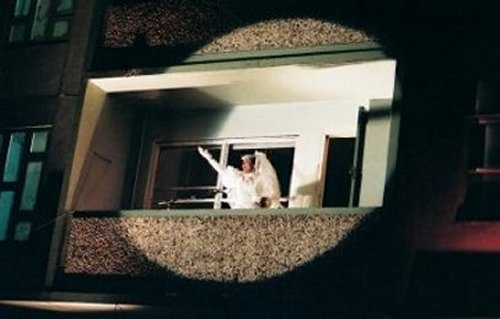

[Above] ReLOCATED - Cranes (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

How did we reconcile the current upheaval with what the Estate was like in its heyday? Old maps provided the missing jigsaw pieces, such as the placement of the demolished highrise, in relation to the twenty-eight four-storey walkups that were going one by one, the one eight-storey walkup with mid-way ramp that was about to go, and the large expanse of trees, including the 100-year-old peppercorns that were felled. We spoke to many of the older tenants who had lived on the Estate for over twenty years, to understand from their perspective the changes that had taken place.

[Above] ReLOCATED - Cranes in Altona Block (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

Toula Tzafaris was one of those tenants, having lived at the highrise 56 Derby Street for thirty-one years, firstly with her husband and daughter and then on her own, after her husband's death and her daughter's marriage. For Mrs. Tzafaris, the changes had meant that some of her friends who lived in the demolished buildings had to move to Footscray and further. She was anxious about her situation. "I am close to everything I need here. I know my way around on the bus and train. They will not demolish my building too, will they?" Mr. Lai Van Nguyen, a 75 year old, former primary school teacher, was stricken by the loss of his friends. He named four of them who would visit him at his highrise flat, and he, in turn, would visit them in their walkup flats. "Our memories are locked into this place, we do not want it destroyed. My friends are old and need help with walking, like me. I don't know where they are. Once they're gone, they are gone forever. I know I will never see them again." Most of these tenants knew very little of what all this "shaking up the foundations" was leading to. They had some idea about "new housing" and "some of it will be sold to private buyers" but they were vague about the details.

It seemed that decisions and details were relayed to the tenants as an after-thought, particularly when noting the manner in which the highrise at 72 Derby Street was demolished in 1998. It was the former Premier Kennett's opinion, that, "The towers detract from Melbourne's skyline and encourage 'anti-social behaviour.'" [1] This led to that Government's resolve to begin a push to rid inner-city living of housing estates, commencing with Kensington. Kennett fulfilled his election promise to bring down at least one of Melbourne's 45 highrise towers but chose the most densely populated and one that had been recently upgraded. Many tenants and community workers were shocked given the lack of tenant involvement in the decision making process and the healthy standard of maintenance for that highrise. [2] As one tenant stated, "Office of Housing just put in a new stove, in my flat, and now I have to leave!"

The Bracks Labour Government continued demolishing the Housing Estate, attempting to soften the final outcome with the 'salt and pepper mix' approach to housing development: where public housing is expediently 'peppered' among a greater number of private dwellings. Becton is contracted to build a total of 195 public units and 421 private units by the year 2011, in the meantime far more than 195 relocated individuals and households want to return back to Kensington. [3]

|

For example, there is single mum Sarah Worn who lives in a spot-purchased house in Braybrook, "I love this place being three bedroom but the outside is an overgrown swamp. It's a paradise for snakes. I'd like to return to Ken, everybody at the shops knows me, even the post office." Also, 11 year old Jane Abdallah, who lives with her father and brother in Coburg at the new development site where Pentridge Prison was situated: "After school there is nothing for me and John to do. No community garden or playground, nothing but some houses with no kids in them." Noemy Martinez who came from El Salvadore and lived with her family at Kensington, and now she lives on her own in a flat in Ascot Vale said, "Back in Kensington when I was sick, there were interpreters at the Community Health Centre which was just up the road; the pharmacy used to deliver my medicines - not anymore." And Mr. Tran who resides in West Footscray, "When I escaped in a boat of 433 people, some of these people from the boat I see in Kensington when I was living there. We are all scattered now but I would prefer to return to Kensington because it is closer to some of them and more central." |

[Above] ReLOCATED - Snake Gully (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

Along with the many who want to return are those tenants who are happily settled and view the Housing Estate as a fond memory, where they first met their wife or took their children to pre-school or got to know which bus to take to the city. There are also those tenants for whom the Estate had dreadful memories of 'druggies' shooting up in stairwells, drunken noisy neighbours and not enough privacy. Still, I spoke with over 250 tenants, residents, community workers, and teachers who had lived or worked at the Housing Estate, and all of them in one way or another missed or reminisced about 'the spirit of the community' on the Estate. This spirit is what Angela Bailey and I sought to reflect through the reLOCATED project.

The reLOCATED arts project is a whirlpool of stories, photographs, opinions and feelings gathered through a varied process of interviews, Polaroid, drama and writing workshops, informal discussions, on-site displays and outreach connections. The process involved working with many local groups, centres and institutions, including children at Kensington Primary School, English language students at the Kensington Neighbourhood House, Horn of Africa women at Kensington Community Centre, and the Elderly Vietnamese Group at McCracken Street, Kensington. Some of our unexpected, but invaluable, 'activities' were making cold-door knocks in Braybrook, playing kick-to-kick with the boys at the Venny (Kensington Adventure Playground), attending 'outings' with the women's group, playing bingo with the elderly at the Community Centre, and surreptitiously entering the boarded up flats with their plastered 'Danger' signs, and rummaging through items left behind.

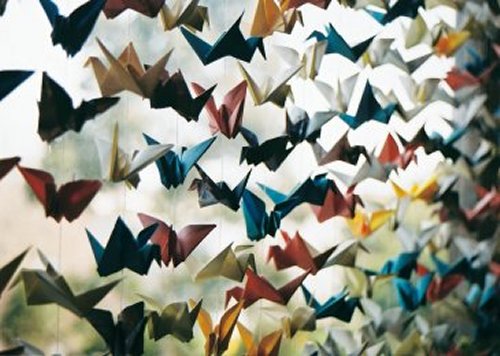

[Above] ReLOCATED 2 (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

In our sneak visits to the Danger zone flats, we found some abandoned treasures; tenants couldn't take everything with them, and so left behind pieces of their lives that we carefully weaved into our stories and images. One of the flats we entered was 314/100 Altona Street. In one of its rooms, it had a rainbow curtain of hundreds of little origami cranes hung together by string and wire. As a photographer, Angela Bailey fell in love with the carefully folded paper creatures. As a writer, I obsessed over the story behind this abandoned treasure. We inspected the flat a little more closely and found a photo of a little girl standing proudly in front of these origami curtains. Did this girl make the cranes? Why? Where was she now? These questions remained unanswered, as we couldn't track where the girl and her family had been relocated.

In the meantime, I researched the Japanese tradition of Senbazuru, which states that once you've made your thousandth origami crane, you can pray for your heart's desire and it will come true. If the little girl made these cranes, what did she pray or wish for? Health? Peace? A happy home?

The little girl, Marilyn Ngo, was eventually found. Through serendipity, her grandfather, Mr. Tran, attended the exhibition at the walkup flat, where he saw the cranes on display. He was so overjoyed that he promptly left to fetch her. When Marilyn entered our exhibition and saw her cranes displayed, she shed some happy tears, but she said her wish will always remain a secret. She lives with her mother, Xi Li Lin, in Yarraville, who told us, "Marilyn is happy and has friends. We're happy with our house and the environment is good".

|

The cranes became Angela Bailey's and my poetic motif as we sifted through notebooks thick with my writing and boxes full of Angela's shots. Like the cranes and its accompanying story, we wanted to develop an outcome with serendipitous layers. We wanted to creatively present our work in a way that reflected the structural demise and reinvention, and the complexity of feeling, evoked through prescribed living and sudden change.

Further, we wanted to acknowledge the Housing Estate as a pivotal piece of contemporary Australian history, so it was imperative that our final presentations be based at the Estate.

In April 2002, we presented an onsite exhibition, where a walkup flat was turned into a living museum and installation space. Apart from a small wardrobe and a large poster of an Essendon football player, Flat 1/36 Derby Street was empty, stripped and ready for demolition. This three-bedroom flat was turned into an exhibition space by keeping the flat's internal structures intact and highlighting life on the Estate through: large scale photographs of the Estate in its various stages; found items left behind in the flats earmarked for demolition; a portrait gallery of tenants and their monologues/dialogues; a wall completely covered with a hand-drawn map of the Estate pre-demolition; the origami crane curtain with its photos and story; and poetry, stories and text on the Estate's history. |

[Above] ReLOCATED - Walkups (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

The following text was placed with actual abandoned items to give a forensic or crime scene aspect to the relocation process:

Flat 714/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Bare except for a Turkish calendar and a view of the dockyards.

Flat 707/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Silver-based graffiti work inside and outside words: "Dissatisfied Youth Fuck Yeh", "Top Story Cuntz", "One, Six, Sixteen".

Flat 511/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Completely empty. Carpet and lino pulled up in parts by maintenance and demolition workers checking for asbestos.

Flat 701/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Chinese calendar with photograph of Mr. Leon Lai, blue pen circles around certain dates, red circles for others - what warrants a red mark? Set of red Christmas baubles in their box.

Flat 304/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Three large posters of luxury cars parked in front of a palace, a mountain peak and a fairytale valley, respectively.

Flat 211/100 Altona Street, 8 November 2001 - Great pile of toys, mostly broken. Playing cards, scattered. Computer keyboard. Clothes, taking up one corner. Ansell condoms, unused. Child's texta marks and scribbles on wall.

That same month, my play (based on the stories and lives of certain tenants who'd once lived on the Estate) was staged on a large grassed area between two walkup buildings. The audience was seated at long banquet tables that were arranged in a square formation, while the performance took place in the middle of the audience, and on various balconies overhead. Tenants, together with several professional actors, performed the script while images of the Estate were projected through windows or blown up and projected onto entire buildings. Familiar sounds, such as those of demolition and pigeons in flight, were amplified throughout the space. The director, Barry Laing, stated "A team of production crew, stage management, sound and light designers, projection artists, performers and tenants of the Estate numbering in excess of forty people gathered to work on the performance. Tenants between the ages of ten years old and into their eighties, many nationalities and language groups including Somali, Vietnamese, Lebanese: and myriad 'Anglo-Australians' are represented among our number ... this 'community' has been extraordinary."

[Above] ReLOCATED - Flat exhibtion (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

Relocated tenants and the wider community, some of which had never set foot in public housing, were invited, and despite the drizzly weather, about 700 people attended each event, that is, the opening of the exhibition space and the performance night.

The final feedback we received from the reference group and the tenants who attended the events, was the need for a 'souvenir'; a book that contained our stories and images about the Estate and their lives. In April 2003, the reLOCATED book [4] was launched, which combined Angela Bailey's photographs with my text. This book documented our entire process and outcomes, including the history of the Estate, and the thoughts of tenants post-relocation. I interweaved throughout was text in the various community languages from the Estate.

There was a large Somali community on the Estate that was broken up and scattered to various outer suburbs. One page of the book was dedicated to this community through photos, selected quotes and a poem:

"The anticipation of relocation may be more traumatic than relocation itself". [5]

"Migrants/refugees may experience involuntary relocation twice: from their war torn birth lands and now". [6]

Mogadishu is burning

the sun does not want to rise

with bombs and guns comes bang-bang-bang

our fear orders our fate

we run where there are no shadows

they feed us papers and hope

we can hear peace calling us ... so far away

our grandmothers pray we do not return

Kensington is dying

the crane is a hungry animal

Bang-bang-bang until there are small rocks

our balcony view changes each day

men in hard hats like men in war dress

they feed us papers and hope

will our new house cradle the earth?

can we ever return?

An initial print run of 1,500 ensured that each tenant-household was posted a copy of the book, whether they were relocated to regional Victoria or stayed on at the Estate. At the launch, the reLOCATED arts project received the national award in local government for innovation and excellence in community services (2002). Over 800 tenants attended that launch, despite many of them having to travel long distances to get there.

Today, the two walkup buildings, from which images were projected and balcony drama took place, have been demolished in the wake of the salt and pepper approach. Becton has erected its display office encased by a white picket fence, where it proffers stage 1 of its development to private buyers, at a commencing cost of $440,000 per unit. Down the road, the retail strip at Macauley Road continues to have its regular facelifts, where coffee shops called Josie become cafes called Kitcch. And the few tenants who remain look out their highrise windows to fewer trees and cultivated allotments.

[Above] ReLOCATED - Demolition (Photo by Angela Bailey, 2003)

The writer's territory versus the communal

When I was working with the public tenants, the Department of Housing and the Tenants Union of Victoria were part of a reference group that helped shape the project's outcome. Sometimes I found myself seesawing between the points of difference from these two contrasting organisations, but I never compromised the scope of the project or the writing that I produced. Sometimes I needed to remind these organisations that I was a 'creative' writer, not a media officer, reporter, copyrighter or journalist. Because many communities are marginalised and supported by welfare infrastructure, the writer ventures into marked territory. Government, not-for-profit and even private organisations determine the parameters of their group's existence through housing, financial support, employment incentives and other welfare benefits. These 'stakeholders' often have prescribed expectations for the writing project and its outcomes. These expectations can get in the way of the writer's journey with the community or they can be an extra voice that the writer can creatively work with.

Communal harmony though is not always possible in this area of writing. Like other writing and artistic worlds, it too has its fair share of shifting ideals, moral dilemmas, copyright and privacy issues. It's a precarious area to work in because there are matters of trust and respect at stake, there are stories and ideas that are not yours, there is the transfer of power to manage, and there is the final question of creative ownership. Who really owns the community-based play or text? It holds the personality, ideas, stories and vocabulary of a community, but it has been written by a commissioned writer and produced by an organisation such as a local council. Arguably all three - community, writer and funding body - have ownership rights to the play/text. This may be a harsh reality to writers who have painstakingly written draft after draft, swerving in and out of their own imagination, taking the play/text from personal anecdote to universal premise. Legally, they could successfully argue that copyright remains with them, unless they've signed a joint copyright agreement. I believe there is no all-encompassing answer to ownership rights. Each situation needs to be considered on several grounds: moral, ethical, professional and legal.

[Above] ReLOCATED - Performance (Photo by Cateherine Acin, 2003)

When I was working in Geelong for the Courthouse Youth Arts Centre on a play, Signatures, with a group of young people ranging in age from twelve to seventeen, authorship of this play became an interesting question. Signatures was written by me using a story I had researched, and it was written in conjunction with a series of intensive workshops with these young people. During these workshops, the group had given me a strong sense of character, which had a big impact on the 'personality' of the play. It felt right for their contribution to be acknowledged in publicity and other public documents. So in the following, albeit longwinded way, everybody's contribution to the writing process was acknowledged:

Signatures was written by Angela Costi in collaboration with the cast of 30 young people from across the Barwon region and a team of professional and emerging artists led by Director Elena Vereker.

On another note, there appears to be a widespread fallacy throughout the literary world that writing from a community context is not 'serious writing' or 'not up to scratch'. This may be the case where the professionally-engaged community writer fails to work openly, intuitively and heartily with the community. But where the writer is stimulating, inspiring and fueling creative energy, the writing that emanates is original, idiosyncratic and suspenseful - all the things that great writing should be. Whether the writer is acting as editor or actually writing the script or text, they need to be using their skills, training and experience to ensure an outcome that will appeal to a wider audience, including those of the literary world.

[Above] ReLOCATED Performance (Photo by Cateherine Acin, 2003)

Having said all this, there is no definitive way of working with communities, and so there is no definitive way of ensuring that both process and outcome will be successful. Like any other arts practice, it needs both the tangible aspects (such as research, experience, skill ...) and the intangible (such as intuition, the unconscious, the chance encounter ...). Probably, the most important element required for a writing project to win the hearts of the community and wider audiences, is for mutual empowerment to take place - where I, as writer, artist, thinker and advocate, am empowered by the community, and, in turn, the community is empowered by me.

ENDNOTES

[1] McKay and Donovan, 'Residents angry at high-rise demolition', The Age, 3 March 1998.

[2] Madden, M., 'Parliamentary Internship Project: A High Rise to Some, A Home to Others: Study of the Relocation of Residents from a Public Housing High Rise Tower in Kensington', 1998, p. 25.

[3] 'Kensington Estate Redevelopment Project: Project Team Newsletter', October 2002

[4] Costi and Bailey, reLOCATED: a tribute to tenants, Kensington Public Housing Estate, City of Melbourne, 2003

[5] Watson, Stress and Old Age, 1980

[6] Madden, A High Rise to Some, A Home to Others, 1998

Small excerpts were taken from two other articles written by Angela Costi:

Writing with communities: is this meant to be a career? Cultural Development Network,

http://culturaldevelopment.net/reading_regular.htm

Writing with communities, Victorian Writer, August/September 2006.

About the Writer Angela Costi

|

Angela Costi's poetry and other writing have been widely published, broadcast and produced. Since 1994, she has been freelancing full time as a writer and editor, completing commissions for organisations including, "ReLOCATED" a full length play and text exhibition for Melbourne City Council based on her writer's residency at the Kensington Housing Commission Estate, "Shimmer", for the City of Darebin and a play inspired by interviews with girls from the working class suburbs of Melbourne. She has written seven staged plays, two of which have been produced for Radio National. She is the author of poetry collections, Dinted Halos (Hit&Miss Publications, 2003) and Prayers for the Wicked (Floodtide Audio, 2005). |

[Above] Photo of Angela Costi by Helena Spyrou, 2005.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.12 (June, 2007) |